Customer Experience Management: 7 Lessons from the Quality Movement

By Bruce Temkin, Managing Partner, Temkin Group

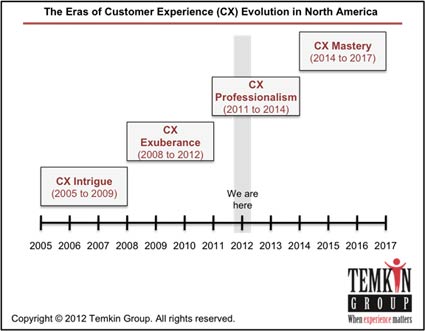

Customer experience (CX) management is evolving from an ad-hoc set of activities to a full-fledged professional discipline.

As the CX movement matures, it resembles the quality movement of the 1980s. Here’s what one of the gurus of quality, Philip Crosby, said in his book Quality Is Free: The Art of Making Quality Certain:

“First, it is necessary to get top management, and therefore lower management, to consider quality a leading part of the operation, a part equal in importance to every other part. Second, I have to find a way to explain what quality is all about so that anyone can understand it and enthusiastically support it.”

That statement is as applicable to customer experience today as it was to quality three decades ago. Given the applicability, here are seven lessons the CX movement can learn from the quality movement:

Nobody owns CX. (Or the corollary, everybody owns it.)

In the early stages of the quality movement, companies appointed quality officers. Many of these execs failed because they were held accountable for quality metrics and, therefore, tried to push quality improvements across the company. The successful execs saw their role more as change facilitators – engaging the entire company in the quality movement. Today’s chief customer officers need to see transformation as their primary objective — and not take personal ownership for improvement in metrics like satisfaction and Net Promoter Score.

Customer experience requires cultural change.

Many U.S. companies in the 1980s put quality circles in place to replicate what they saw happening in Japan. But the culture in many firms was dramatically different than within Japanese firms. Companies did not get much from these efforts, because they didn’t have the ingrained mechanisms for taking action based on recommendations from the quality circles. Discrete efforts need to be part of a larger, longer-term process for ingraining the principles of good customer experience in the DNA of the company.

Customer experience requires process change.

Quality efforts of the 1980s grew into the process re-engineering fad of the 1990s. As business guru and author Michael Hammer showcased in his 1994 book Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, large-scale improvements within a company require a change to its processes. That perspective remains as valid today as it was back then. Customer experience efforts, therefore, need to incorporate process reengineering techniques. That’s why these efforts must be directly connected to any Six Sigma or process change initiatives within the company.

Customer experience requires discipline.

Ad-hoc approaches can solve isolated problems, but systemic change requires a much more disciplined approach. That’s why the quality movement created tools and techniques — many of which are still used in corporate Six Sigma efforts. These new approaches were necessary to establish effective, repeatable and scalable methods. A key portion of the effort was around training employees on how to use these new techniques. Customer experience efforts will also require training around new techniques. This type of discipline is described in Four Customer Experience Core Competencies and The Six Ds of a closed-loop VoC Program.

Upstream issues cause downstream problems.

This is a key understanding. The place where a problem is identified (a defective product or a bad experience) is often not the place where systemic solutions need to occur. For instance, a problem with a computer may be caused by a faulty battery supplier and not the PC manufacturer. A bad experience at an airline ticket counter may be caused by ticketing business rules and not by the agent. So improvements need to encompass more than just front-line employees and customer-facing processes.

Employees are a key asset in the battle.

The quality movement recognized that people involved with a process had a unique perspective for spotting problems and identifying potential solutions. So many of the tools and techniques created during the quality movement tap into this important asset: employees. Customer experience efforts must systematically incorporate what front-line employees know about customer behavior, preferences and problems, as well as what other people in the organization know about related processes.

Executive involvement is essential.

For all of the items listed above, improvements (in quality then and in customer experience now) require a concerted effort by the senior executive team. It cannot be a secondary item on the list of priorities. Change is not easy. To ensure the corporate resolve and commitment to make the required changes, customer experience efforts need to be one of the company’s top efforts. Senior executives can’t just be “supportive,” they need to be truly committed to and involved with the effort.

Corporations removed major quality defects in the '80s and re-engineered business processes in the '90s. Now it’s time to take on the next big challenge: customer experience.

Bruce Temkin is a customer experience transformist & managing partner for the Temkin Group. He is also chair of the Customer Experience Professionals Association and writes for the Customer Experience Matters blog.

Public relations, digital marketing, journalism, copywriting. I have done it all so I am able to communicate any information in a professional manner. Recent work includes creating compelling digital content, and applying SEO strategies to increase website performance. I am a skilled copy editor who can manage budgets and people.